BOOK YOUR WORKSHOP TODAY

All posts published here are presented as casual conversation pieces to provoke thought in some direction or another, they do not necessarily represent fixed opinions of the Inner Council, as our work exists beyond the spectrum of bound statement and singular clause.

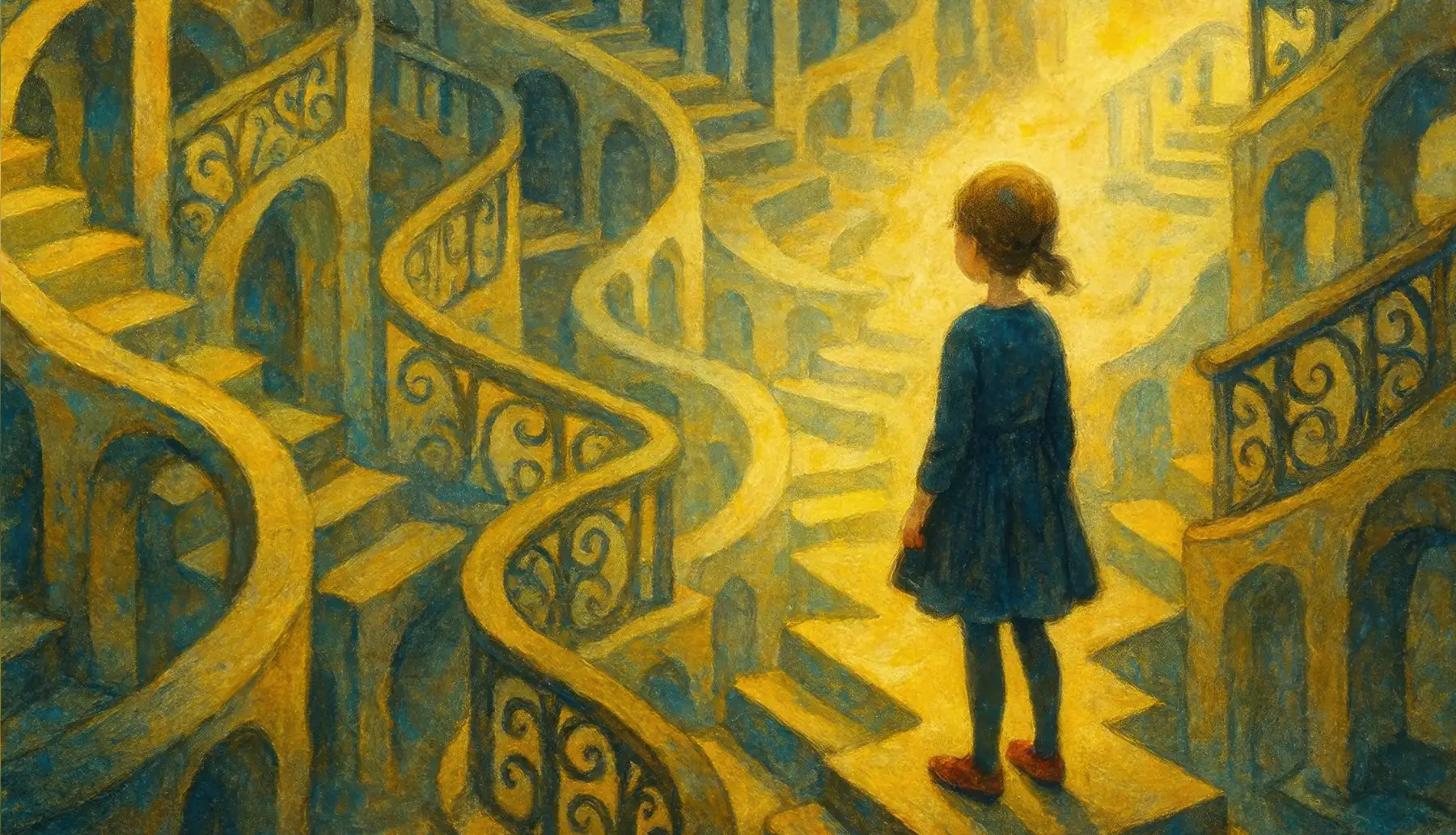

The Paralysing Effect of Guilt

Guilt is an energetic emotion that weaves through generations and cauterises the expressive functions required for full life and creativity. As such, guilt can be weaponised, devastating the soul’s journey. We often think of behavioural conditioning and emotional triggers as episodic—only re-emerging when familiar circumstances arise—but guilt is different. Its imprint can compromise our sense of safety on a near-permanent basis. We may wake each morning already constricted, instinctively avoiding actions that might invite negative judgement, as though an internal program were designed to keep us small, cautious, and afraid.

The importance of safety becomes clearer when viewed through cell biology. A single biological cell exhibits two basic external behaviours: attraction or repulsion. It cannot do both at once. In human terms, this translates to either retracted survival mode or outward expression and engagement. The perception we carry of our environment, our implicit belief about what the world will do to us, determines which state we inhabit. Chronic guilt locks the system into retraction, suppressing vitality, creativity, and confidence.

Robert M. Sapolsky explores this dynamic extensively in Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, alongside his biographical work A Primate’s Memoir, tracing how prolonged stress responses, originally designed for short-term survival, begin to erode health, perception, and agency when they become chronic. His work helps illuminate how internalised threat states, once adaptive, can quietly reshape a life when left unexamined.

For reasons rarely examined, we live within a culture that inoculates human potential with a pervasive sense of wrong-doing. The English language itself reflects this burden. Where many languages employ a relatively neutral term such as culpable, English leans heavily on guilt and guilty, words saturated with moral weight. As a result, much of our present energy is spent managing the past. We avoid conflict, speak in half-truths, over-justify our existence, and apologise pre-emptively. Some fall into a deep helper-syndrome, organising their entire lives around earning approval, allowing guilt to dominate motivation and quietly contaminate thought from morning to night.

James Joyce understood this cultural paralysis intimately. It took him twelve years to publish Dubliners, a work shaped by his conviction that guilt had seeped so deeply into everyday life that it had rendered a people inwardly motionless. He described the book as a revealing looking glass, believing that only through honest recognition could collective release become possible.

Guilt is not merely a concern with the past; it is a present-moment immobilization about a past event. And the degree of immobilization can run from mild upset to severe depression. If you are simply learning from your past, and vowing to avoid the repetition of some specific behavior, this is not guilt. You experience guilt only when you are prevented from taking action now as a result of having behaved in a certain way previously. – Wayne W. Dyer

Guilt as a Value Signal

What is rarely spoken about is that guilt does not arise from our lowest or most destructive parts. It arises from our highest. Guilt is generated by the very capacity that recognises value, relationship, and care. If there were no sense of worth, no awareness of impact, no internal orientation toward goodness, guilt could not exist at all. Indifference does not feel guilt. Callousness does not feel guilt. Only a psyche that knows meaning does.

Martin Heidegger approached guilt not as moral failure, but as an existential signal arising from conscience itself. For him, guilt was not primarily about having done something wrong, but about sensing a misalignment with one’s own responsibility and potential for right relation. In this sense, guilt is not evidence of defect, but proof that an inner orientation toward integrity is still alive.

This is where guilt becomes tragically misunderstood. Instead of being recognised as a signal of conscience and relational intelligence, it is interpreted as proof of defect. The psyche turns a message of care into an identity of failure. The result is paralysis. Rather than restoring value, guilt freezes the system, trapping a life-affirming signal inside self-judgement.

Seen clearly, guilt is asking for repair, not punishment. It carries an implicit optimism: that something matters enough to be tended to, that coherence can be restored, that dignity is not lost beyond reach. Guilt appears because the inner world already knows that alignment is possible. When guilt is met with understanding rather than condemnation, its weight begins to lift. Movement returns. Choice returns. The same inner capacity that recognised wrongness also holds the intelligence for reconciliation and growth. In this way, guilt is not the end of vitality but a threshold—an invitation to step out of paralysis and back into responsible, living relationship with oneself and the world.

The Weight of Guilt

In many Indigenous languages, there is no standalone word equivalent to guilt at all. Instead, experience is described in terms of imbalance, broken relationship, or loss of alignment. These are not conditions of personal defect, but situations that invite response and restoration. When something moves out of harmony, the emphasis naturally turns toward what is required to bring it back into balance, rather than toward punishment or self-condemnation.

Across Romance languages, a similar orientation can be felt. Words such as culpa or culpabilité tend to describe responsibility for an action rather than a flaw of being. The language allows for accountability without collapsing identity into failure, keeping attention on repair rather than on moral stain. In Japanese, what English speakers might call guilt is often expressed through concepts related to social disruption or loss of harmony, where the emotional weight is carried situationally and collectively. The focus moves toward reintegration and restored relationship, not inward self-attack.

German offers an important nuance. The word Schuld can mean guilt, debt, or obligation, allowing responsibility to be held without immediate moral accusation. This linguistic flexibility made it possible for philosophers such as Heidegger to speak of guilt as an existential condition—a call to responsibility—rather than as a verdict of wrongdoing.

English, by contrast, gathers many of these meanings into a single, condensed term. Guilt in English often fuses action, blame, morality, and identity, giving the experience a particular density. When responsibility becomes indistinguishable from personal worth, the signal meant to guide repair can instead immobilise. It is this weight—carried silently and repeatedly—that James Joyce recognised as paralysing a culture. Not because people lacked conscience, but because the language through which conscience was felt had become too heavy to move with.

The Inner Child's role

Within Inner Council therapy, we side-step the behavioural system in order to observe, from an objective standpoint, what is occurring and where the original programming took hold. Through this perspective, conditioning can be neutralised and the role guilt has played across a life can be accurately recognised.

Unlike approaches that rely on force or cognitive insistence, the Inner Child reveals material only when enthusiasm, readiness, and trust are present. She offers fragments, symbols, and clues that assemble into integration when responsibility has matured enough to receive them. The work is initiated and paced by the subconscious itself, allowing each chapter of the narrative to unfold in its proper time.

Through deep regression and reframing, layers of psychic residue are gently cleared, restoring sovereignty and clarity. Guilt is never a fixed identity; it is always transitory, lingering only until the surrounding context is fully understood. Beneath it, we sense that there is more—another story waiting to be told.

The Inner Child is already there, waiting for contact, provision, and protection. When we meet her with openness, willingness, and trust in our own capacity to care, the rest begins to move naturally. Healing follows not through force, but through relationship.

Daily Inner Child guilt release practice

Objective: To gently observe, release, and reframe guilt, while strengthening your relationship with your Inner Child.

Step 1: Grounding (1–2 minutes)

- Sit comfortably and close your eyes.

- Take 5 slow, deep breaths, feeling your body settle into the chair or floor.

- Imagine roots growing from your feet into the earth, connecting you to stability and safety.

Step 2: Visualize Your Inner Child (1–2 minutes)

- Picture your Inner Child in front of you, noticing their age, posture, and facial expression.

- Observe any signs of worry, shame, or guilt they may carry.

- Take a moment to feel empathy and compassion for them.

Step 3: Dialogue with Compassion (2–3 minutes)

- Ask your Inner Child:

- “What are you feeling guilty about?”

- “What do you need to feel safe and free?”

- Respond kindly, offering reassurance:

- “It’s okay, you are safe now.”

- “You did the best you could at the time.”

- “You are loved and worthy exactly as you are.”

Step 4: Release and Reframe (2 minutes)

- Imagine the guilt as a dark cloud, heavy weight, or chain.

- Slowly release it with each exhale, imagining it dissolving or floating away.

- Replace it with a warm light, joy, or freedom filling your Inner Child.

- Invite your Inner Child to breathe in this new energy, feeling lighter and more empowered.

Step 5: Integration and Commitment (1–2 minutes)

- Hold your Inner Child close or link hands, acknowledging their courage.

- Reflect on what lessons the guilt brought without letting it immobilize you.

- Affirm together:

- “We are free to act in the present with love and clarity.”

- “We are learning, growing, and safe to be ourselves.”

Optional Step 6: Journaling

- After the exercise, write down any insights, emotions, or messages from your Inner Child.

- Note patterns of guilt and small victories in releasing them over time.

Click here for more Inner Child Exercises.

Visit our Inner Child Workshop page to find out more.