BOOK YOUR WORKSHOP TODAY

All posts published here are presented as casual conversation pieces to provoke thought in some direction or another, they do not necessarily represent fixed opinions of the Inner Council, as our work exists beyond the spectrum of bound statement and singular clause.

A Jungian guide to ego-death, rebirth and intuition—exploring how identity dissolves, the Child archetype emerges, and the psyche moves toward wholeness.

Key Takeaways

- Ego-death is a natural stage in psychological and spiritual development.

- Identity dissolves when it can no longer contain the psyche’s deeper growth.

- Rebirth emerges through the tension of opposites via Jung’s transcendent function.

- The Child archetype appears as a symbol of unity and psychic renewal.

- Intuition strengthens as the psyche reorganises around the Self.

- Inner Child work bridges personal healing with archetypal transformation.

Why Talk About Ego-Death?

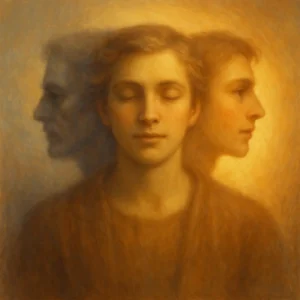

The dissolving, emerging and intuitive faces of the psyche — a visual arc of ego-death and rebirth, where the self loosens its old identity and a deeper awareness begins to take form.

Ego-death is a term that drifts between worlds. In mystical circles it is spoken of in whispers, a kind of initiatory dissolution reserved for saints, ascetics, or those who have travelled far beyond the boundaries of ordinary consciousness. In psychological circles it is treated cautiously, often equated with psychosis, fragmentation, or pathological break. And in mainstream conversation it is frequently trivialised—flattened into jargon, aestheticised into social-media mysticism, or dismissed entirely as esoteric delusion. Yet ego-death is neither rare nor exotic. It is happening quietly, continuously, across the entire arc of our lives.

Every time we shed an outdated role, outgrow a version of ourselves, lose a worldview, release a long-held stance, or confront the collapse of our certainties—we undergo a form of ego-death. Most of these dissolutions are subtle: a change of taste, a severed belonging, a disillusionment, a realisation that the maps we trusted no longer represent the territory. But whether dramatic or ordinary, ego-death is woven into the natural maturation of human identity. There is a simple reason for this: the ego is not a static entity but a temporary arrangement of identity, assembled to help us navigate a particular developmental stage. Like scaffolding used during construction, it is meant to be adjusted, reconfigured, or dismantled when its purpose is complete. Problems arise only when we cling to the scaffolding as if it were the building itself.

This is why ego-death is often uncomfortable. It challenges our sense of continuity, stability, and self-reference. It disrupts the illusion that the “I” we carry is fixed, central, or permanent. It pulls back the veil of certainty we use to orient ourselves in the world. But this discomfort is also why ego-death matters so deeply. Beneath every dissolution is the possibility of re-birth—a reorganisation of identity, a broadening of perception, a softening of defensive structure, and the emergence of a deeper alignment with our intuitive and subtle capacities. Ego-death is one of the ways the psyche remembers itself.

In modern society, however, we lack the frameworks that once held these transitions. Traditional cultures had rites of passage, mythic initiations, communal witnessing, and symbolic languages that contextualised the death-rebirth cycle. They understood that identity is not a straight line but an ongoing dance of shedding and renewal, mirroring nature’s seasonal rhythms. Today, without those narrative structures, ego-death often feels like failure, collapse, or malfunction. We pathologise what older cultures regarded as initiation. We try to stabilise what is meant to evolve. We cling to identities that have outlived their usefulness and suppress the intuitive, imaginal, and mystical sensibilities that are meant to resurface at later stages of life.

So why talk about ego-death now? Because we are living in a time when psychic transitions are accelerating, both individually and collectively. People are shedding identities at a pace unprecedented in modern history: careers collapsing, roles shifting, values rearranging, relationship structures dissolving, beliefs decentralising, and cultural narratives losing coherence. The ground beneath the ego is less stable than ever. And in the absence of communal initiation, individuals must turn inward. We must learn to understand the architecture of identity—how it forms, how it dissolves, and how to consciously participate in its evolution.

Ego-death is not an abstract philosophical curiosity. It is a lived psychological necessity. It is the mechanism through which the psyche grows, adapts, heals, and reincorporates the lost or forgotten aspects of the soul—especially the Inner Child, whose essence often becomes trapped beneath layers of adaptation and survival. To understand ego-death is to understand how the inner world renews itself. It is to recognise the intelligence behind collapse. It is to see rebirth not as a dramatic mystical event, but as a quiet, iterative, lifelong process.

This is why we begin here. Not with the metaphysics. Not with the mythology. Not even with the intuition that will emerge later. We begin with ego-death because it is the threshold—the necessary doorway through which transformation becomes possible.

The Perennial View: How Identity Is Born

Long before modern psychology attempted to describe the formation of identity, ancient cultures articulated a metaphysical understanding of the self as something layered, permeable, and fundamentally connected to a larger field of being. Across continents and millennia, a consistent intuition emerged: that the essence of the human being is not born fragmented, nor inherently separate, but arrives already enfolded in a greater unity. This perennial view appears in the Upanishads, in Taoist cosmology, in the Mayan Popol Vuh, in the Hermetic texts of Egypt and Greece, and in countless Indigenous creation stories that describe humanity as emerging from a primordial oneness. Identity, in this sense, is not given at birth—it is constructed during the descent into individuality.

According to these ancient frameworks, the child begins life close to the source. Its perception is undifferentiated, intuitive, and relational. The infant does not yet experience itself as a bounded entity; its early consciousness resembles a field, not a point. In Western developmental psychology this is sometimes framed as “symbiosis” or “pre-egoic unity,” but older traditions describe it more accurately as participation mystique—a natural state of embeddedness in the cosmos. The ego forms gradually as the child differentiates from mother, from environment, from the undivided field of early perception. This differentiation is necessary, but it comes at a cost: the boundaries that enable autonomy also narrow the aperture of awareness.

By the time we reach adolescence, the ego has crystallised into a complex network of stories, attachments, defensive identities, and culturally sanctioned roles. We learn who we are by learning what is expected of us. Family dynamics imprint the first layer, followed by schooling, peers, cultural narratives, and the subtle pressures of belonging. The ego becomes a tapestry woven from inherited scripts and survival strategies—an improvisation performed with impressive conviction. But beneath this patchwork lies the deeper self, the unconditioned field of being that preceded differentiation.

This view helps us understand why so many people feel estranged from themselves in adulthood. The ego is not the enemy; it is simply incomplete. It was never designed to carry the full weight of our identity. It is a provisional structure, meant to help us navigate a particular developmental stage. Traditional societies understood this intuitively. They created rites of passage that facilitated the transition from egoic identity to a more expanded, soul-rooted mode of being. Without these rituals, the ego tends to ossify, clinging to its roles long after they have outlived their purpose. This is one of the core themes explored in Initiation, Soul Loss, and the Inner Village: Rebuilding the Rite of Passage in a Fractured World, which examines what happens when a culture loses the mechanisms that once guided identity into maturity.

The perennial traditions also emphasise that identity is not merely personal but cosmological. We are not isolated psyches drifting in a meaningless void; we are expressions of a larger intelligence manifesting through countless forms. The ego is the lens through which this intelligence focuses itself for a time, but it is not the source. This distinction becomes essential when we discuss ego-death. What dissolves during ego-death is not the self but the framing device. The collapse of identity is not a collapse of being; it is a loosening of the conceptual boundaries that falsely define who we imagine ourselves to be.

Modern closed-system thinking, however, struggles with this concept. Much of contemporary psychology remains rooted in materialist assumptions that reduce identity to neural architecture or behavioural conditioning. Within such a framework, ego-death appears either pathological or metaphorical. Yet countless individuals undergoing profound spiritual or psychological transformation describe experiences that align far more closely with the perennial view: a stripping away of false identities, a sense of returning to an original essence, a widening of awareness, and an undoing of the self-referential loops that bind consciousness to defensive structure.

When we reclaim the perennial perspective, ego-death becomes demystified. It is no longer a dramatic, otherworldly event but a natural maturation of consciousness—a shift from a narrow self-concept into a wider, more relational mode of awareness. It also becomes easier to see how this connects to inner child work. For it is the child who first embodied this non-dual, intuitive mode of perception. And it is the ego, over decades, that gradually obscured that original clarity.

Thus, returning to the perennial view is not an abstract metaphysical exercise. It is a way of recovering a forgotten developmental truth: that identity is layered, that consciousness evolves through cycles of differentiation and de-differentiation, and that ego-death is not an annihilation but a remembering. It is the rediscovery of the self beneath the story.

III. Trauma, Fear, and the Survival of the Ego

The ego does not emerge in a vacuum. It is shaped in the crucible of early experience, formed through the delicate interplay of need, environment, recognition, and threat. In its healthiest form, the ego is a flexible interface—capable of adapting, expanding, and renegotiating itself as the individual encounters new experiences. But when early life contains trauma, inconsistency, or emotional unpredictability, the ego hardens prematurely. It becomes less like a permeable membrane and more like a defensive shell. Its primary function shifts from navigation to survival.

Trauma teaches the ego one core lesson: the world is dangerous and I must remain vigilant. This vigilance becomes identity. A child exposed to overwhelming emotional force learns to anticipate risk before it arrives. It learns to scan, to brace, to contract its inner world so that shock lands on a smaller surface area. In adulthood, these adaptive strategies are often mistaken for personality traits—hyper-independence, perfectionism, emotional detachment, overthinking, or chronic people-pleasing. Yet beneath these patterns lies a simple truth: the ego learned long ago that collapse was not an option.

This defensive orientation creates a fundamental problem for later stages of psychological and spiritual development. Ego-death requires softening, loosening, and trust in dissolution—qualities that trauma-conditioned egos experience as unsafe. The very idea of surrendering a piece of identity can feel existentially threatening, not because the identity is precious, but because the ego equates yielding with annihilation. In this sense, trauma does not just wound the psyche; it interrupts the natural rhythm of identity’s evolution.

This is where fear enters the picture—not fear of external danger, but fear of internal change. The ego becomes committed to preserving familiar patterns, even when those patterns cause suffering. It clings to the known because the unknown has once been catastrophic. The irony is that the ego is usually trying to protect an identity that was never designed to last. Fear makes the temporary feel permanent.

And yet, this defensive ego is not the enemy. It is a guardian that once kept the child alive. Its rigidity is evidence of devotion. But devotion becomes limitation when the environment changes and the ego cannot update its strategies. Modern psychology often labels these rigidities as disorders, but they are better understood as outdated survival codes—remnants of an earlier stage of life, still executing their original programming.

Ego-death, then, becomes a paradoxical invitation: the very structure that fears dissolution must allow dissolution for healing to occur. This is why the death-rebirth process can feel like an internal standoff. One part of the psyche senses the possibility of expansion; another part perceives only danger. The instinct to protect collides with the impulse to grow.

This tension is not a sign of failure but a sign of readiness. It means the self has reached the limits of its protective architecture. It means the deeper layers—intuition, imagination, subtle perception—are pressing upward, trying to reclaim psychic territory that trauma once occupied. The fear that arises is not a warning but a threshold. Fear appears precisely where transformation becomes possible.

This is also where Inner Child work re-enters the conversation. Trauma-generated ego structures often formed in childhood, and it is the child who first suffered the overwhelm that caused the ego to harden. When we approach ego-death with compassion rather than force, we implicitly acknowledge that the ego is not a tyrant but a protector shaped by the child’s experiences. The fear of dissolution is, in essence, the child’s fear of disappearing again.

Recognising this softens the entire process. Ego-death becomes less like an execution and more like a rite of passage—one that must involve the child’s voice, the child’s safety, and the child’s inclusion in the emerging self. When the child is reassured, the ego can release its grip. When the ego releases its grip, identity can evolve. And when identity evolves, intuition and higher perception have room to unfold.

Thus trauma, fear, and ego-survival are not obstacles to the journey—they are the terrain through which the journey passes. To understand them is to understand why ego-death is difficult, why it is necessary, and why it ultimately restores the lost complexity of the inner world.

The Hero’s Journey and Archetypal Rebirth

Every culture tells the same story: a person lives an ordinary life until something cracks the surface. A calling appears. A threshold opens. The familiar dissolves. What follows is not simply adventure—it is identity dismantling itself.

Joseph Campbell called this sequence the Hero’s Journey, but it is older than mythology. It is the blueprint by which the psyche renews itself. Something in us must die so that something else can be born. In myth, this death often arrives as a symbolic descent—into the underworld, the forest, the night sea. But in ordinary life it appears in far quieter forms: the end of a relationship, the collapse of a belief, the shedding of a role that no longer fits.

The moment the old identity falters, a gap opens. The ego loosens. The deeper self steps forward. The hero crosses a threshold not just into “the unknown,” but into a part of their own psyche they have not yet inhabited. This is why all heroic tales feel strangely personal; they are projections of an inner architecture we instinctively recognise.

Nietzsche described this process through his “Three Transformations”: the camel who carries the weight of the world, the lion who rebels against it, and finally the child—innocent, playful, newly capable of creation. Myth is meta-aware. It knows the sequence before we do. It knows that the child waits at the end of the journey, not the beginning.

We often undergo small versions of this cycle without noticing. We stop identifying with the fashions, music, or collective tribes that once defined us. We drift from one worldview into another. These are miniature ego-deaths, gentle rehearsals for the larger transitions that life inevitably brings.

But occasionally a major identity falls away—suddenly, without preparation. These moments feel cataclysmic, but from the perspective of myth they are initiations. The psyche is performing a necessary dismantling. A door opens beneath the surface, and the hero is pulled through—whether willing or not.

The reason the Hero’s Journey resonates so deeply is because it reveals a truth we often forget: identity is cyclical. We do not grow in straight lines. We grow in spirals, circles, and returns. Each descent triggers a rebirth. Each death clears space for something more essential. And each transformation brings us closer to the part of us that is timeless—the child, the soul, the subtle intelligence that guides us beyond the limits of ordinary identity.

The myths tell us what psychology sometimes forgets: that falling apart is a stage of becoming. And recognising this meta-pattern is itself an initiation.

The Unchosen Ego-Death: When Life Forces Transformation

Not every descent begins with a calling. Some begin with collapse.

In mythic language, these are the moments when the ground gives way beneath the hero and the story no longer waits for consent. A loved one dies. A relationship fractures. A future we worked toward dissolves overnight. Illness, betrayal, crisis—these are the thresholds that arrive uninvited, prying open the door the ego has kept tightly sealed.

Psychologically, these events dismantle the identity structures that once provided coherence. The ego depends on continuity: “This is who I am, this is where I’m going, this is how life is supposed to unfold.” When one of those pillars is removed, the self enters freefall. The mind scrambles to reassemble meaning. The nervous system searches for stability. The psyche enters a liminal state—no longer who it was, not yet who it will become.

Myth calls this the night-sea journey: a plunge into waters that strip away the old form. But the psyche knows this territory intimately. It has built-in mechanisms for renewal. When a major identity collapses, the deeper layers of the self—what Jung called the “transcendent function”—begin to reorganise inner life, slowly and invisibly, to accommodate a new configuration of being.

This is why moments of profound loss often bring with them a strange, disorienting spaciousness. The ego experiences this as emptiness or meaninglessness, but myth sees something else: a blank canvas. A psychic clearing. A field in which old structures have burned away, leaving raw possibility. In the symbolism of the Hero’s Journey, this is the belly of the whale or the underworld chamber—the place where transformation is not only possible but inevitable.

Plant medicine ceremonies often mirror this unchosen descent with uncanny precision. They dissolve the narrative scaffolding of the ego, temporarily returning the psyche to a pre-conceptual state. For many, the aftermath brings the same fragile, luminous vulnerability that follows a major life rupture. Both experiences deliver the individual into psychic openness—a state psychologists might call regression in service of the ego, but myth calls rebirth.

Yet the unchosen ego-death differs from the chosen one in one critical way: it does not feel empowering. The individual is thrust into change rather than stepping toward it. What feels like spiritual initiation from the outside often feels like annihilation from within. But this internal devastation is not evidence of failure; it is evidence of transition. The psyche is shedding a form that can no longer carry it forward.

This is why attitude becomes the quiet alchemy that determines what follows. When we resist the collapse, the ego tightens, clings, and hardens. The descent becomes suffering. But when we meet the collapse with even the smallest measure of willingness—an openness to re-evaluation, a curiosity about the unfamiliar, a readiness to reorganise—the same descent becomes initiation.

The mythic and psychological perspectives converge here:

the breakdown is the threshold.

Not a punishment. Not an accident.

A portal.

Unchosen ego-death is painful because it strips away identities we did not plan to release. But it also carries an unexpected gift: it returns us to the raw material of selfhood. It loosens the stories we inherited or constructed. It allows the deeper, older intelligence of the psyche to take the lead. And it invites the emergence of a more authentic, intuitive identity—one aligned not with the ego’s survival strategies, but with the soul’s larger arc of becoming.

Attitude as Alchemy: Choosing How We Undergo Ego-Death

Once the old identity has been shaken loose—whether by choice or by circumstance—the psyche enters a state of profound plasticity. This is the moment myth describes as the forging of the new self, the place where the raw material of the soul is heated, softened, and reshaped. But the outcome of this reshaping depends on something deceptively simple: how we meet the experience.

Psychologically, attitude is not mere mindset; it is a configuration of the entire psyche—emotion, expectation, belief, nervous system, imagination—orienting itself toward what is happening. A rigid attitude contracts around pain and tries to restore the previous order. A receptive attitude softens into the unknown and allows new configurations to emerge. The difference between these two postures is the difference between suffering and initiation. This is why, in myth, the hero’s courage is not the absence of fear but a willingness to walk forward while fear is present. The hero does not choose the underworld; they choose how to meet the underworld. Even in stories where the descent is forced—Orpheus losing Eurydice, Psyche losing Eros, Inanna being stripped at each gate—the transformation only occurs when the character accepts the necessity of what is happening. Resistance prolongs the trial; acceptance unlocks its meaning.

In psychological terms, this acceptance is not resignation. It is an attunement to the deeper intelligence shaping the experience. The ego sees collapse as catastrophe; the psyche sees collapse as reorganization. When we shift our attitude to align with this inner process, we stop trying to rebuild the old identity and start listening for the contours of the new one. This shift often happens quietly. A subtle willingness to feel. A small softening around a fear. A moment of recognition that what is falling apart may not need to be restored. These micro-movements of openness create space for transformation to take root. Alchemy was never about force; it was about correct orientation. A vessel cracks under pressure but transforms when heat is met with openness.

In practical terms, the change in attitude might look like this:

- trusting that confusion is part of the process

- allowing emotions to surface rather than suppressing them

- loosening the need for immediate clarity

- seeing disruption as information rather than threat

- recognising that a “self” is not being destroyed but redefined

This psychological reorientation mirrors what myth teaches: that ego-death is not an execution but a surrender of form. The identity that dissolves is only the version that can no longer carry the soul forward. What remains—and what emerges—has deeper roots. Crucially, this shift invites the Inner Child back into the process. The child knows how to trust the unknown. The child knows how to be curious, receptive, imaginative. When attitude softens, the child becomes an ally in the transition, providing the intuitive sensitivity that the ego has long suppressed. In this way, attitude becomes alchemy not only for the adult self but for the entire inner system.

Adopting this posture allows the ego-death to unfold with less contraction and more coherence. It becomes something the psyche participates in rather than something done to it. The collapse becomes a corridor. The darkness becomes a gateway. And the unknown becomes a field in which the next form of identity—more spacious, more intuitive, more aligned—can take shape.

Integral Theory and the Natural Maturation of Consciousness

Human consciousness does not remain static across the lifespan. It develops in stages, each with its own patterns of perception, meaning-making, emotional regulation, and identity formation. In early life, the psyche is fluid and imaginal; in adolescence and early adulthood it becomes increasingly rational, structured, and self-protective. With maturity, these structures soften again, allowing intuition, subtle awareness, and transpersonal perception to rise. This developmental arc is not random—it is one of the most well-established findings in developmental psychology, cross-cultural anthropology, and consciousness studies.

Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory synthesises dozens of developmental models—Piaget, Kohlberg, Loevinger, Kegan, Graves, and others—into a coherent evolutionary trajectory of the self. While their language differs, their underlying insight is the same: the ego is a stage, not a conclusion. Its task is to organise personal experience into a stable identity capable of navigating the world. But as the individual matures, the ego’s structures become too narrow for the increasing complexity of inner life, and the psyche begins to press outward, seeking wider frames of meaning.

Around midlife—roughly the mid-30s onward—many people naturally begin transitioning from the “rational-egoic” stage into a more pluralistic, intuitive, and integrative form of consciousness. This shift is often triggered by experiences that exceed the ego’s explanatory models: grief, love, failure, crisis, synchronicity, deep creativity, altered states, or the emergence of unexpected emotional or spiritual sensitivities. The ego interprets these events as destabilising. Developmental psychology sees them as signals that the psyche is attempting to grow.

In these later stages, the mind becomes more flexible and less dogmatic. Identity becomes less tied to external validation and more centred in authenticity. The individual grows comfortable holding paradox, navigating uncertainty, and perceiving the subtle layers of experience that earlier stages filtered out. Intuition strengthens, not as a mystical gift but as a developmental competence—the result of the psyche integrating emotional, cognitive, somatic, and relational intelligence into a unified field of perception.

From a developmental perspective, ego-death is the mechanism by which consciousness transitions between these stages. When an identity structure reaches the limits of its usefulness, the psyche begins to deconstruct it from within. This deconstruction can feel like crisis, but its purpose is adaptive. The old identity cannot carry the increasing complexity, nuance, and sensitivity emerging from deeper layers of the self. In this sense, ego-death is not an aberration—it is evidence of maturation.

This developmental view also clarifies why the Inner Child becomes significant at this stage. The early years of life contain perceptual capacities—intuition, play, imagination, direct relational awareness—that are suppressed during the rational-egoic phase but are essential for higher stages of development. As consciousness evolves beyond rational boundaries, it must reclaim these early capacities, not regressively but integratively. The child’s perceptual world becomes the raw material for advanced adult awareness.

Thus, integral development is not linear—it is recursive. The psyche circles back to earlier layers, retrieves what was lost or split off, integrates it into a larger framework, and then moves forward with expanded capacity. The ego experiences this as dissolution. Developmental psychology recognises it as transition. And myth, as we’ve seen, frames it as initiation.

When we understand the natural maturation of consciousness, ego-death ceases to be frightening. It becomes an expected phase in the unfolding of identity. A signpost indicating that the psyche is ready to expand beyond its previous limits. A developmental threshold through which the intuitive and subtle dimensions of the self begin to emerge.

Intuition: The Next Organ of Perception

As the ego’s old structures loosen and identity begins to soften, a different mode of perception rises to the surface—one that is older than rational thought, yet newly available in a more mature, integrated form. This mode is intuition. In childhood, intuition appears as raw sensitivity: an unfiltered awareness of emotion, atmosphere, subtle cues, and relational fields. In adulthood, once the ego relaxes its rigid grip, intuition re-emerges not as regression but as expansion, a widening of perception that includes the somatic, emotional, symbolic, and imaginal dimensions that rational consciousness previously pushed to the margins.

Psychologically, intuition is not a mystical anomaly but an advanced integration of multiple forms of intelligence. Neuroscience shows that the body processes far more sensory information than the conscious mind can track, and that emotional and somatic data are often interpreted milliseconds before cognition arrives. What we call intuition is the psyche’s ability to synthesise this vast, pre-verbal stream of information into meaningful impressions. It is perception occurring before thought.

Somatically, intuition is anchored in the body’s subtle signals: tension in the chest, warmth in the abdomen, tingles along the arms, the quality of breath, shifts in the solar plexus, the quiet pull toward or away from something unseen. These signals are not random—they are the nervous system’s atmospheric readings, gathering micro-information from the environment, from relational fields, and from unconscious processes. When the mind slows enough to feel these signals, intuition becomes a palpable sense-organ.

Yet intuition is not only somatic; it is also mythic. It comes with images, metaphors, symbolic flashes, and dreamlike impressions that feel as though they arise from a deeper stratum of the psyche. Carl Jung called this the “objective psyche,” a layer of mind that expresses itself in archetypal imagery and non-linear insight. Intuition draws from this imaginal reservoir as readily as it draws from the body. It is both a sensory and symbolic intelligence.

This is why intuition often feels like a message from a wiser part of ourselves—or, in mythic language, from the soul. It bypasses the ego’s linear reasoning and goes straight to pattern recognition, relational truth, and energetic coherence. In myth, intuition is the helper that appears at the threshold: Athena whispering to Odysseus, the fairy godmother guiding Cinderella, the animal companion who knows the safe path through the forest. These figures personify the intuitive function, the inner guide that emerges precisely when identity is shifting.

Developmentally, intuition strengthens as the psyche moves beyond the rational-egoic stage into a more plural, integrative consciousness. It requires the capacity to hold ambiguity without anxiety, to trust subtle perception, and to engage both imagination and sensation without collapsing into either. This is why intuition often expands naturally in midlife or after major ego-death experiences—the psyche has freed enough internal bandwidth to perceive what was always there but previously overshadowed by the ego’s defensive vigilance.

Crucially, intuition bridges the adult and the child. The child perceives intuitively because it has not yet learned to filter perception. The adult perceives intuitively when it has learned to filter perception—but can now choose when to suspend those filters. Intuition, therefore, is not a return to childhood but a reconciliation with it, an integration of early capacities into a larger, more stable adult framework.

This balanced mode of perception—somatic, imaginal, psychological—allows the individual to navigate life not solely through logic or identity, but through a deeper attunement to context, inner truth, and subtle meaning. It opens the psyche to forms of guidance that cannot be reduced to analysis: the sense of “rightness,” the quiet knowing, the embodied yes or no, the symbolic nudge that arrives without explanation.

In the aftermath of ego-death, intuition becomes the compass. It is the organ that perceives the path before the path becomes visible.

Jung’s Rebirth: The Archetypal Child and the Re-Centering of the Psyche

The archetypal Child rises from the fertile darkness, carrying the first spark of wholeness — a reminder that rebirth begins with returning to the most essential part of ourselves.

Carl Jung understood rebirth not as a poetic metaphor or a dramatic spiritual event, but as a psychic necessity woven into the architecture of human development. Rebirth is the psyche’s way of reorganising itself when an existing identity has reached the limits of its usefulness. It is the movement of the ego away from its narrow centre of gravity and toward a deeper organising principle: the Self. This shift is not linear but cyclical, and it is marked by the emergence of one of the most powerful archetypes in Jung’s entire system—the Child.

To Jung, the child archetype was not simply a memory of our early years or a nostalgic psychological imprint. It was the symbol of unity, the bringer of wholeness, the representation of a future personality emerging from the tension of the opposites. The child embodies both the pre-conscious and the post-conscious essence of the human being: it is the state we begin in before differentiation, and the state we move toward when consciousness matures beyond the oppositions that once defined it. In this sense, the child is alpha and omega—beginning and end—origin and destiny.

This archetypal child has little to do with the personal wounded child of biographical memory, though the two often intersect. The personal inner child carries the emotional residues of upbringing, but the archetypal child carries the symbolic intelligence of the psyche itself. When it appears, it signals a profound reorganization: the ego is no longer the sovereign centre of personality, and the Self is beginning to take its place.

In Jung’s model, rebirth unfolds through a predictable psychic sequence. The individual first identifies with their personal infantilism—the feelings of abandonment, injury, or immaturity that emerge when old structures break down. This stage is emotionally raw and often confused. Following this comes the identification with the hero, a compensatory inflation that momentarily bolsters the ego. Here the individual sees themselves as special, chosen, uniquely burdened, or destined—a subtle but seductive ego-defense. Only after the heroic inflation breaks does the true Child emerge: not sentimental, not regressive, but archetypal—a symbol of synthesis, the future personality calling the individual toward wholeness.

The mechanism behind this transformation is what Jung termed the transcendent function, the dynamic tension created when conscious and unconscious attitudes confront one another without collapse. When held long enough, this tension generates a “living third thing”—a new psychological attitude that reconciles the opposites and propels the individual into a higher level of integration. Rebirth, then, is not the result of dramatic destruction, but of deep psychic dialogue facilitated by the symbol-making capacities of the unconscious.

This is why symbolic images, fantasies, and visions appear with such force during periods of ego-dissolution. Jung insisted that these fantasies are not “made up”—they are autonomous expressions of the unconscious, containing instructions, compensations, and insights that consciousness cannot generate on its own. Through active imagination, the individual engages these inner figures, not as hallucinations, but as real psychological presences with which a relationship must be formed. The transformation does not occur through interpretation alone, but through the lived experience of encountering the unconscious and allowing it to reshape identity.

Ego-death often amplifies synchronicity—meaningful coincidences that signal alignment between inner and outer processes. Jung recognised these not as supernatural anomalies but as indicators that the unconscious is pressing toward consciousness, reorganising the psyche and attending to the individual in symbolic ways. In the context of rebirth, synchronicity acts like a psychic compass: it reveals that the inner and outer worlds are momentarily aligned in the service of transformation.

At the heart of this entire process is the emergence of the Child Archetype. It is the symbol that reconciles what was split. It unites the personal with the collective, the conscious with the unconscious, the instinctual with the spiritual. The child is the mediator, the guide, the promise of a future personality that is more whole, more rooted, more unified than the fragmented ego that preceded it.

This is where Jung’s theory intersects profoundly with Inner Child work. When a person undergoes ego-death—whether through crisis, spiritual awakening, or the natural maturation of consciousness—the opportunity arises for the archetypal child to appear. Through regression, imagination, or direct symbolic experience, a bridge forms between the personal inner child (who holds emotional truth) and the archetypal child (who holds psychic wholeness). When these two layers come into dialogue, the individual moves from fragmentation toward integration. The shift of psychic gravity from ego to Self begins.

Rebirth, in the Jungian sense, is not merely becoming someone new. It is becoming more wholly oneself—recovering the primordial unity that was once pre-conscious and transforming it into a post-conscious synthesis. It is loosening the structures that once defended us and allowing the deeper, wiser, timeless center to emerge. It is the psyche’s continual movement toward wholeness, guided by the same archetypal intelligence that has directed human transformation for millennia.

In this way, ego-death becomes not an end but a re-entry point into the eternal child, the symbol of our unity and the source of our future becoming.

How Ego-Death Relates to Inner Child Work

In the stillness of the awakened Self, the many forms of the Inner Child gather — each a facet of our history, imagination and intuition, now reintegrated into consciousness.

If we follow the arc of ego-death through mythology, developmental psychology, and Jungian depth psychology, a striking pattern emerges: the dissolution of identity creates the conditions for the Child to return. Not the biographical child alone, nor merely the wounded child of our early conditioning, but the deeper archetypal Child — the symbol of unity, wholeness, and psychic renewal.

Ego-death strips the psyche of its accumulated identities, its worn-out roles, its defensive positions. As these constructs fall away, consciousness enters a liminal state, a space where old forms no longer hold but new structures have not yet taken shape. This psychic openness is the inner equivalent of the mythic underworld — the chamber of dissolution where the next form of the self is incubating. It is in this interval that the Inner Child begins to stir.

From the perspective of Inner Child work, ego-death softens the adult’s rigid identifications, making room for the child’s emotional truth to finally surface. The protective strategies that once shielded the child — avoidance, overthinking, perfectionism, cynicism, hyper-independence — loosen their grip. The psyche becomes more permeable. The adult self becomes more receptive. As the ego’s boundaries thin, the child can finally step forward and speak.

But this emergence has a second layer, illuminated by Jung: the archetypal Child appears as well. Where the personal child carries biographical wounds and unmet needs, the archetypal child carries symbolic intelligence — the instinct toward integration, creativity, unity, and transformation. It is the force that Jung saw as both the beginning and the end of psychic evolution. When the personal and archetypal child come into relationship, the result is not regression; it is individuation.

Ego-death acts as the clearing that allows this meeting to occur.

Rebirth is the process of integrating what emerges from that meeting.

Psychologically, this integration takes many forms:

- rediscovering imagination and sensory intuition

- healing emotional wounds that the adult identity suppressed

- reclaiming spontaneity, curiosity, and presence

- resolving old complexes through conscious engagement

- letting the child’s truth guide new attitudes and decisions

- allowing the child’s perceptual sensitivity to inform adult intuition

These are not sentimental qualities — they are developmental capacities.

As consciousness evolves, it must retrieve the perceptual gifts of early childhood: emotional immediacy, symbolic awareness, subtle sensing, and direct relationality. These capacities then become transformed into adult intuition, empathy, creativity, and inner authority.

This is why Inner Child work becomes essential after ego-death. Without reconciling the child, the ego attempts to rebuild itself in the same narrow patterns that previously led to collapse. But when we work with the child, a different identity emerges — one that is more flexible, truthful, responsive, and attuned to the deeper psyche. In Jungian terms, this marks the shift from an ego-centered life to a Self-centered life.

At this stage, synchronicities increase, imagination deepens, dreams become more vivid, and symbolic perception heightens. These are the signs that the psyche is reorganising itself around a new centre of gravity. The child becomes the guide, and the adult becomes the steward. Together they form a unity that neither could achieve alone.

Thus, ego-death leads naturally, almost inevitably, into Inner Child work.

Rebirth requires the child’s presence.

Intuition requires the child’s sensitivity.

Individuation requires the child’s symbolic intelligence.

Wholeness requires the child’s unity.

When we understand this, ego-death ceases to be a rupture and becomes a rite of passage — a psychic initiation that allows the most essential part of ourselves to step forward and take its rightful place at the centre of our being.

The child returns, not to regress, but to lead us home.

Closing: The Cycle Will Return Again

Ego-death is not a singular event but a rhythm woven into the fabric of a human life. Identities rise and fall, meanings dissolve and re-form, old selves fade while new ones gather shape beneath the surface. Each cycle brings us into deeper relationship with the psyche’s core intelligence, revealing that death and renewal are not opposites but partners in the same unfolding movement.

In myth, the hero does not descend only once. Descent is a returning pattern, a spiral that draws the soul closer to its own center. The same is true psychologically. Every ego-death clears another layer of debris. Every rebirth strengthens the connection to the Self. Every encounter with the Inner Child deepens the unity between the conscious and the unconscious, between what we have been and what we are becoming.

This rhythm continues across the lifespan. Some cycles are gentle, arriving like subtle tides that shift our inner coastline. Others are seismic, reshaping the terrain entirely. But all share the same underlying purpose: to move us toward greater coherence, authenticity, and wholeness. To remind us that identity is fluid. To reveal that the psyche is capable of far more than the ego imagines.

And in each return, the Child waits. The symbol of unity. The custodian of our original essence. The guide who carries the map to the next horizon.

Ego-death initiates the cycle.

Rebirth continues it.

Intuition navigates it.

The Inner Child completes it.

And the pattern begins again—each time bringing us a little closer to the center of who we truly are.

Recommended Reading

Ritual: Power, Healing and Community — Malidoma Patrice Somé

A profound exploration of ritual as a living technology for psychological integration, ancestral healing and communal initiation. Somé reveals how traditional rites create meaning, restore balance and reconnect individuals to the spiritual and communal forces that sustain wholeness.

The Wisdom of the Serpent: The Myths of Death, Rebirth, and Resurrection — Joseph L. Henderson & Maud Oakes

A powerful Jungian study of serpent symbolism across cultures, illuminating the universal mythic pattern of death and renewal. Henderson and Oakes show how serpent imagery encodes the psyche’s capacity for transformation, regeneration and the cyclical shedding of old identity.

No Boundary: Eastern and Western Approaches to Personal Growth — Ken Wilber

One of Wilber’s most accessible works, mapping the spectrum of consciousness from ego-bound identity to non-dual awareness. A clear, integrative guide to dissolving psychological boundaries and understanding the developmental journey toward unity, insight and inner freedom.

The Red Book — C.G. Jung

Jung’s intimate record of his encounters with the unconscious, revealing the raw process of active imagination that shaped his entire psychology. Through mythic visions and dialogues with inner figures, the book demonstrates how symbolic encounter becomes the engine of rebirth, individuation and psychic integration.

The Inner Council & Jungian Vision — The Inner Council

A comprehensive exposition of the Inner Council framework, showing how Jung’s concepts of the Child archetype, the transcendent function and the imaginal psyche translate into practical methods of inner work. Essential for understanding the architecture, symbolism and psychological logic behind the Inner Council’s approach to transformation.